July 2024

MRG high-school researchers present their work at the 2024 Northeast Natural History Conference

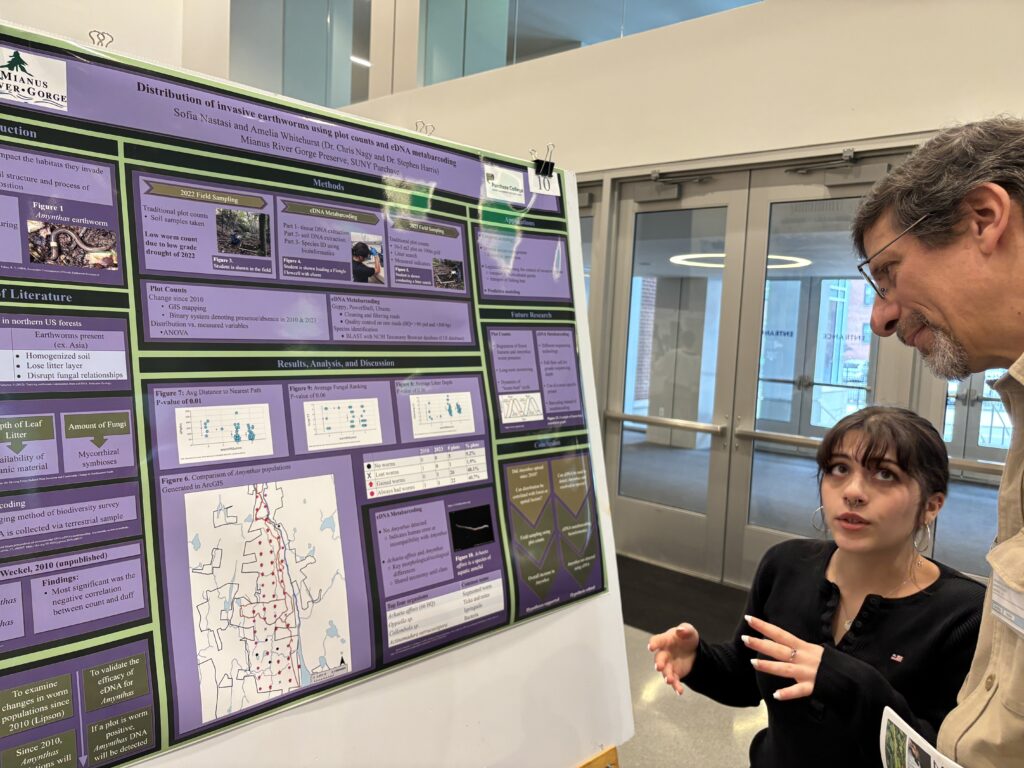

Two of our graduating seniors in our Wildlife Technician Program presented their completed research at the 2024 Northeast Natural History Conference in April.

Alex Thompson (Blind Brook HS) gave a lecture on his study of frogs in several wetlands and vernal pools. He used our new acoustic recorders to record frog calls during the spring breeding season at 12 wetlands on MRG property. Because each species of frog has a unique call, Alex could use audio recordings to determine what species of frogs live in each wetland.

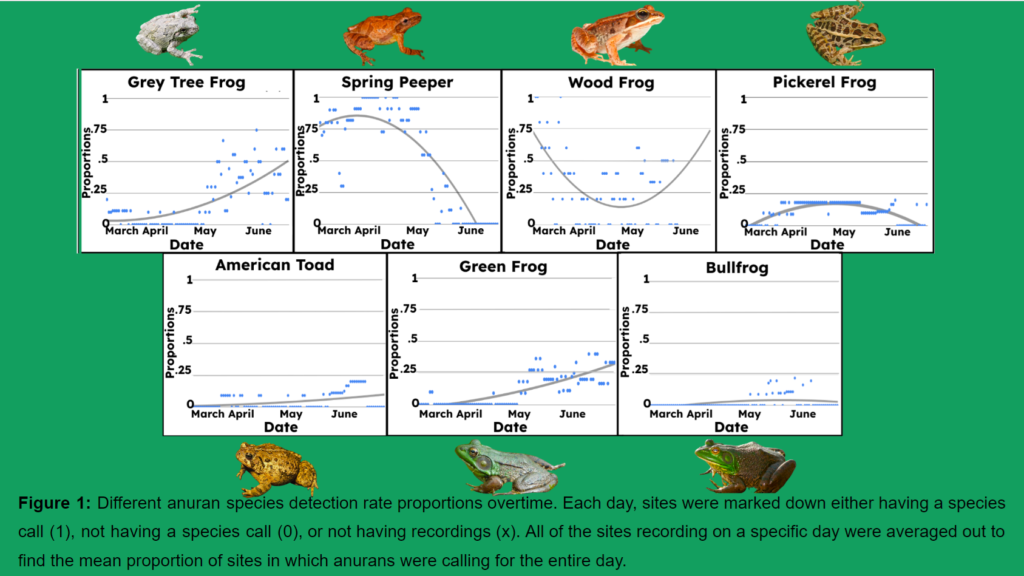

Alex detected 7 species of frogs in his sample pools: gray treefrogs, wood frogs, American toads, pickerel frogs, green frogs, bullfrogs, and spring peepers. Rare species we hoped to perhaps find such as chorus and cricket frogs were not detected.

Alex then compared the species’ respective presence and absence patterns with habitat features such as the type (permanent or vernal) and size of the water body. He found that American toads and pickerel frogs were found more often in permanent pools than in vernal (seasonal) pools. Pickerel frogs, green frogs, bullfrogs, and spring peepers were present more often in large wetlands than small ones, while American toads were found in smaller pools.

He was also interested in when each species seemed to call the most across the spring and summer, to help plan future monitoring across all of our pools and wetlands. Depending on the species of interest, one may want to monitor at different times (Figure 1).

Sofia Nastasi (Yorktown HS) studied the spread of invasive earthworms of the genus Amynthas. Her study was a follow-up to a study performed by a past high school researcher, Harry Lipson, in 2010.

Amynthas earthworms are invasive in North America and despite their size can have tremendous negative impacts on the soil of our forests. Generally, forests in the northeast evolved without earthworms after the last ice age, and their introduction by humans disrupts soil processes and, in turn, the plant and fungal communities above- and below-ground.

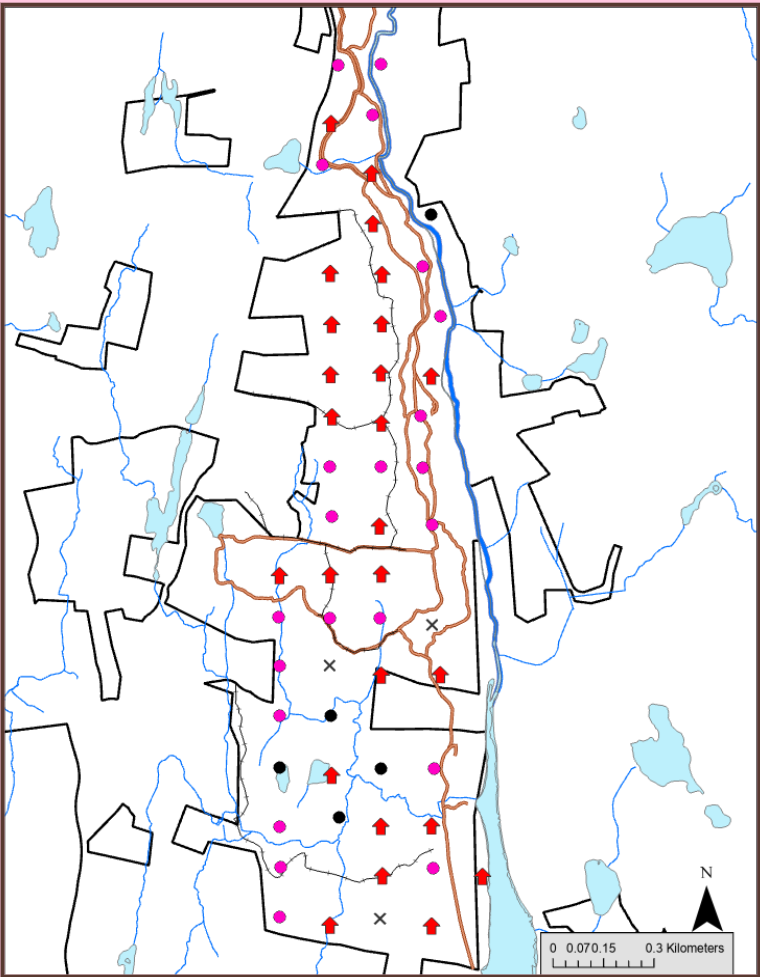

In 2022 and 2023, Sofia re-visited 57 plots that were surveyed for these worms in 2009 and 2010. She, surprisingly, found less than 10 worms total in 2022, but when she repeated the survey in 2023 found worms in abundance as we expected. This indicated that worm populations can be very variable, but recover quickly. Overall, Sofia found that by 2023 the worms had spread to many of the plots that did not have them in 2010, and are now, unfortunately, present across the Preserve.

Comparison of Amynthas sp. presence/absence 2010 to 2023.

Red arrows: not detected in 2010, present in 2023

Pink circles: Detected in 2010 and 2023

Black circles: Not detected in 2010, detected in 2023

X’s: Not detected both years

Both Alex and Sofia graduate this year. Alex will be heading to Cornell University and Sofia will be attending SUNY Binghampton.

You can watch Alex’s lecture on our Youtube channel.

To learn more about our high school researchers, check out the Wildlife Technician Program page.

Sofia’s research was made possible by a grant from the Rusticus Garden Club, which has supported the WTP for over a decade.

MRG takes part in global study on wildlife response to human activity during COVID

MRG staff helped co-author a recent paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution that examined how wildlife responded to shifts in human activity during COVID.

The study, headed by researchers from the University of British Columbia and North Carolina State, used camera trap data from 146 studies across 37 countries, including the Mianus River Gorge Preserve.

The study used camera trap photos of both wildlife and humans to examine how human activity in preserves, parks, and other greenspaces changed from 2019 to February 2020 (pre-COVID) until the end of 2020 (during COVID and when many communities were under lockdown restrictions).

Human activity was expected to decrease overall during COVID restrictions, but it turned out to vary greatly from place to place. Still, many places saw severe changes in human activity (whether up or down) during this tumultuous period, and these dramatic shifts allowed researchers to compare changes in human behavior to potential shifts in wildlife behavior across many species. The study focused on species that can be sampled well with camera traps: mammals larger than 1 kg.

When humans increased their outdoor activity, animals in urban areas seemed to shift their activity heavily to the nighttime while still using the same areas, but animals in rural areas decreased their overall activity altogether — potentially either leaving these areas altogether or sacrificing foraging time.

In the end, different species of mammals responded differently to increased human activity, but some interesting patterns emerged. In general, activity in wild mammals in response to human activity varied by both trophic position and landscape.

Large herbivores (e.g., in North America, deer, elk, bison) increased their activity in areas with higher human activity, while large carnivores decreased their activity. Simultaneously, animals in areas that were more developed (urban) generally increased their activity when human activity increased, but this activity tended to be nocturnal.

Locally, the Gorge saw a drastic increase in human activity during lockdown. Many more people came to use our trails, as outdoor activities were basically the only options for recreation outside the home. In response to this, white-tailed deer seemed to become more nocturnal and lower their activity levels (contradicting the global trend for large herbivores). Red fox became more nocturnal while coyotes became more diurnal.

This analysis was very complex and it highlights many implications for wildlife ecology, conservation, and human-wildlife coexistence. For urban animals — that increased their nocturnal activity with greater human activity — nocturnal refugia should be maintained so these animals have alternative places to go when people are around. This can help limit close encounters with people. Since predators tended to avoid or reduce activity in areas with high human activity, and large herbivores tended to do the opposite, the latter may be using human activity as a way to avoid predators. This study is also yet another piece of evidence that many species are very sensitive to human activity, and these still need large, intact areas where people do not go.

Check out the full paper at Nature Ecology and Evolution

You can learn more about Snapshot USA here

John Peregrin (RAP) evaluates the success of MRG’s HWA treatments

MRG awards grants to graduate students doing a thesis in applied ecology, conservation, natural resource management, or similar fields in our Research Assistantship Program. In 2021, John Peregrin (MA, Columbia) was awarded a RAP grant to evaluate our efforts to limit hemlock wooly adelgid (HWA) with basal bark application of insecticide to eastern hemlock trees in MRG and Blackrock Forest.

HWA is an exotic, invasive aphid that feeds on hemlock trees. Since it was introduced to eastern North America in the 1950’s HWA has devastated the eastern hemlock in the northeast, as well as having similar effects on the Carolina hemlock down south. In cooperation with Cornell’s NYS Hemlock Initiative, MRG began treating its eastern hemlocks with a basal bark application of two insecticides (as recommended by the NYSHI). We have treated (and re-treated after 5 years) over 2,700 trees in the Gorge since 2016.

John’s research sought to compare treated and untreated trees to see if adelgid presence was reduced or eliminated in treated trees, compared to untreated ones, and if this in turn led to greater growth in the untreated trees. He studied hemlocks here at the Gorge as well as on a newly-treated group of trees in Blackrock Forest. From samples of the upper branches of paired treated and untreated hemlocks with a shotgun — yes, that is a real technique — in 2021 and 2022, John could measure adelgid presence, new growth, foliar nutrient uptake, and several other measures of tree health and growth.

John finished his thesis last fall, and his findings supported the efficacy of the treatment program, at least at MRG. HWA densities were significantly lower on treated trees versus untreated trees, and new growth increased 8.9% in treated trees. At Blackrock, there was no significant differences between treated and untreated trees, possibly because the more recent first treatment at Blackrock had not really taken effect yet.

Spraying all of our hemlocks every 5-7 years is a tremendous endeavor. The NYSHI is developing and testing a number of biocontrols — other organisms that potentially could be released and prey upon HWA, limiting its impacts on the hemlock trees. NYSHI has released two of these biocontrols here and our newest RAP awardee, Nick Dietschler, who works at NYSHI, and his WTP mentee, Keira Borello, are tracking the survival and dispersal of these biocontrols.

Our old-growth hemlock forest is one of our top priorities here at MRG, and we are working hard to find a solution to the HWA issue. Stay tuned for more updates!

To learn more about the NYSI: New York State Hemlock Initiative

MRG’s Research Assistantship Program for PhD and Master’s students