November 2022

Do trails and recreation impact wildlife?

MRG supported projects and co-authored a number of papers this year that examined the relationship of hiking trails, human activity, and wildlife distribution and behavior.

The first noteworthy study on this topic was WTP researcher Charlotte Klurfield’s (formerly from Ossining HS) study on hiking and wildlife patterns in the Gorge. Charlotte and MRG staff monitored 18 cameras in our Preserve for over a year to look at how animals responded to people hiking our trails. Cameras were placed on trail, 50 yards off, and 200 yards off of trails and the seasonal and daily activity of various wildlife species was compared to the activity of hikers. As a group, coyotes, red fox, and bobcats were photographed more often on trail-side cameras than elsewhere, but this activity was exclusively nocturnal. Thus, mammalian predators selected human-made trails as movement corridors but still avoid humans temporally. Conversely, deer were substantially less likely to be photographed near trails than far away regardless of time of day or whether trails were open or not. You can watch Charlotte’s lecture at the Northeast Natural History Conference on our youtube channel here.

In a recent article, Human presence drives bobcat interactions among the U.S. carnivore guild (Hubbard et al. 2022), researchers used a national camera trap dataset from the Snapshot USA program collected in 2019 to examine how bobcats respond to the presence of dominant (e.g., wolves and cougars) and subordinate (red and gray foxes) carnivores. Included in these analyses was human activity and human population density along with a suite of environmental factors.

Overall, Hubbard et al. found that bobcats have complex relationships with other carnivores. Bobcats showed strong spatial avoidance of larger and presumably more dominant species (wolves, cougars, and coyotes), but this avoidance effect was less intense in areas of high human activity. In other words, bobcats seemed to perceive humans as a greater threat and prioritized avoiding people, even when large predators were present.

This paper was based on the thesis research of Tru Hubbard at Northern Michigan University. Camera data from MRG — via Snapshot USA — was used in the paper. Chris Nagy assisted with parts of the analysis and manuscript prep.

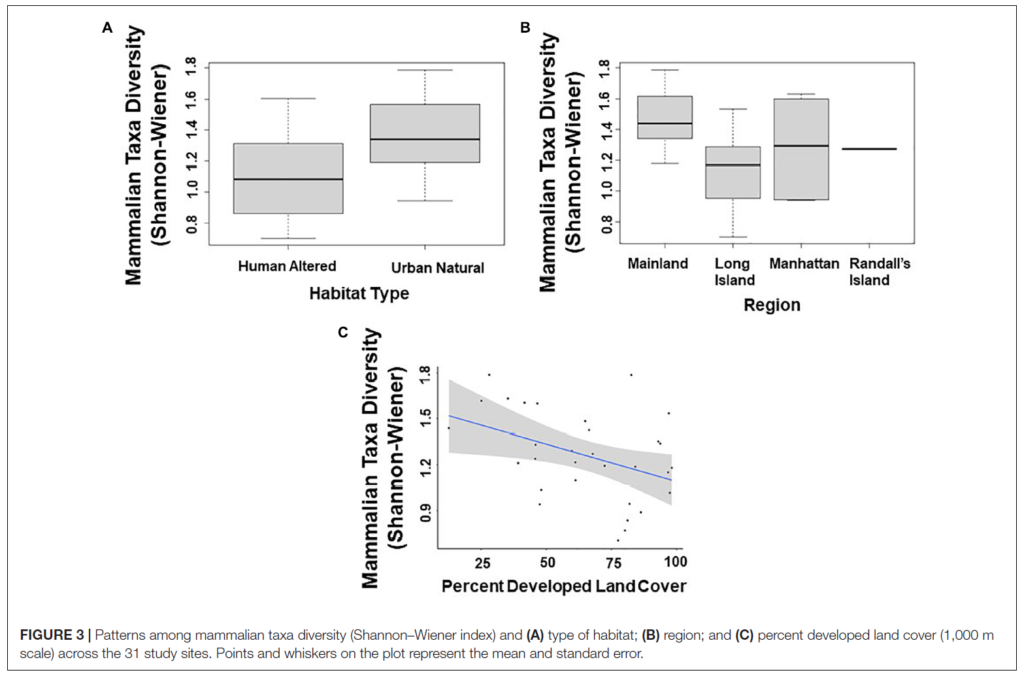

Finally, Predictors of Mammalian Diversity in the New York Metropolitan Area (Bradfield et al. 2022), examined a 4-year dataset of camera trap images collected across 31 greenspaces in NYC from 2016 to 2019 as part of MRG’s Gotham Coyote Project. Researchers found that human impacts affect urban wildlife populations at multiple scales. First, the ways in which humans have modified the urban landscape and the landscape within greenspaces affected the overall wildlife diversity found in various parks: parks with more undeveloped land had greater wildlife diversity compared to parks with more developed areas such as lawns and playgrounds.

Greater population density in the area around parks also negatively affected wildlife diversity. Again, this partnership leveraged field work and camera data collected by MRG with analysis by academic colleagues. This paper was part of Angelinna Bradfield’s thesis work at Queens College, supervised by Dr. David Lahti at Queens College and Dr. Bobby Habig at Mercy College. MRG’s Chris Nagy also assisted with data organization and analysis, as well as manuscript prep.

The impacts of trails, hikers, and overall human activity are complex across even the relatively limited set of species (medium and large mammals) these studies examined. Overall, most wildlife seek to avoid humans and this affects their behavior and distribution. Different species accomplish this goal in different ways, the main options being avoiding people temporally (e.g., becoming nocturnal), spatially (e.g., avoiding trails altogether), or a combination. Even small trails for just simple hiking (i.e., no dogs, bikes, or other recreational vehicles) altered the behavior of some species. And on larger scales, highly manicured or developed greenspace support fewer species than undeveloped open space.

A recording of Charlotte’s lecture at the 2022 Northeast Natural History Conference is available here.

For a full list of our academic publications, please visit our Scientific Publications page.

If you want a copy of any of the papers, please email chris@mianus.org

An instance of recent coyote-dog hybridization in NYC

MRG staff recently co-authored a paper on the genetics of a particular coyote family that lived in Queens in 2016. This family was the first documented instance of coyotes denning and successfully raising young on Long Island ever, and was reported in a paper in Checklist in 2017 by our Gotham Coyote team.

This family was, unfortunately, designated as a safety hazard by the Port Authority as they were entering the grounds of LaGuardia airport and were lethally removed. The carcasses however were stored at the American Museum of Natural History and, at the very least, proved to be very valuable specimens.

Our colleagues at the AMNH, Anthony Caragiulo, Neil Duncan, and Mark Weckel, and Princeton University, Stephen J. Gaughran and Bridgett vonHoldt found interesting ancestry for a few of these coyotes. While the mother’s genetic makeup was similar to typical eastern coyotes, with most of her ancestry of coyote lineage with a small portion of wolf and/or dog heritage from many generations back, the adult male had far more dog-specific alleles — nearly 50% — and this hybridization was from a single generation ago. In other words, the father of this family was a first generation coyote-dog hybrid!

In addition, two of the pups were effectively 75% coyote and 25% dog — the proportions you would expect from the offspring of a coyote-dog + regular coyote cross.

And finally, the adult male and one of the pups carried two mutations that, in dogs, are known to be associated with hypersociability towards humans. Another, unrelated coyote from a larger sample also had these particular genetic insertions, which indicates that these behavior-related genes may be present in the overall population in some substantial portion.

While it is important to note that this is a single instance of a recent dog-coyote cross, it leads to many other questions: will this happen more often as coyotes move into Long Island and face limited mate choices? Will these dog-related alleles that lead to hypersociability towards people increase in prevalence in the coyote population? If so, will it help coyotes navigate the urban world, or lead to human-coyote problems?

You can read the paper in the journal Genes.

For more info on the Gotham Coyote Project, see GCP’s facebook or our website.

Also check out the vonHoldt lab at Princeton for more on evolutionary genomics of canids and other taxa

Sarah Walkley’s RAP research finds new river otter vocalizations

Sarah Walkley, an MRG RAP awardee, recently completed her dissertation on North American river otter vocalizations. For her Ph.D., Sarah examined wild populations of river otters living in both California and New York, including within the MRG Preserve and elsewhere in the Mianus Watershed. Sarah used video- and audio-capable camera traps placed at latrine sites (communal locations that river otters use to defecate and leave scent) to record otter vocalizations and behavior.

Sarah recorded four call types — which she termed chuckle, hah, chirp, and whine — in both California and New York otters, and found an additional call (chirpwhine) in only the California population. The behaviors of the otters while emitting these different calls were recorded and compared to see if certain calls indicated particular functions or messages the otters were communicating to each other. Sarah found that different calls were used when otters were alone, in pairs, and in larger groups; for example, chirps were used only when otters were solo, while chuckles and whines were used in groups of 3 or more. This study not only contributed to the limited knowledge that exists on the North American river otter vocalization repertoire, but also bridges the gap between animal acoustics and behavior, providing behavioral context for this elusive species’ vocalizations in the wild and human care.

To learn more about Sarah’s research, and to see some videos of otters making these vocalizations, visit wildotteracoustics.org.